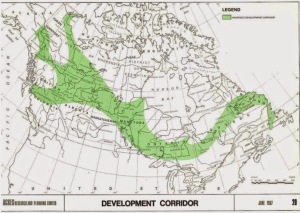

Between Canada’s border-hugging south and our great white north runs a ribbon of undeveloped territory indicated on this map in green. This undulating swath of land contains the riches of our nation; everything from cobalt and copper in Labrador, gold and hydro in Quebec, chromite and copper in Ontario, potash in Saskatchewan, oil and gas in Alberta and B.C.

It makes great sense to develop this mid-Canada corridor in an orderly fashion. Also, we need to prepare land and infrastructure for the influx of climate change migrants that will flock to Canada. A hodge-podge of development is now the norm says John Vahan Nostrand in Walrus magazine.

“As an architect and planner with special interest in mining regions and towns, I’ve seen the damage first-hand.” The standard approach to resource extraction is to build a temporary settlement, extract the resource and move on.

Majority world countries are more susceptible. Labour is cheap and environmental standards lax. However, Canada is not immune to the damage of resource extraction; even more vulnerable after the Harper government weakened environmental laws with the passage of bills C-38 and C-45. Now only one per cent of our waterways are protected.

“The Conservative agenda,” says NDP Megan Leslie, “systematically dismantles any environmental legislation that might restrict unbridled expansion of their resource exploitation agenda.”

The explosion of Fort McMurray is an example of what unregulated development looks like. While 73,000 live in Fort McMurray, almost that many live in surrounding camps.

“At current rates of production,” warns Van Nostrand of oil sands extraction, “the timeline for its full exploitation is estimated at more than 200 years, and yet existing First Nations, Métis, and non-Aboriginal communities are being built up on haphazard, short term basis.”

Communities don’t benefit from the resulting chaos. Workers in the camps spend sizable paycheques in other cities, provinces, and countries. The workforce is primarily male and the businesses that spring up are hardly family oriented: drugs, prostitution, and strip clubs.

The money used to set up these temporary, malfunctioning, camps could be used to build permanent towns and cities. The cost of a temporary camp for 1,200 workers is $50 million. A rational approach would be to set up permanent family-friendly communities with economies that actually work; where wages are spent locally and the social costs are reduced.

Developing our middle corridor will require some changes in governance as well. As things now stand, municipal regions pay for the costs of runaway expansion while reaping little of the rewards.

Melissa Blake, the mayor of the municipal region containing Fort McMurray, complains that the city pays for infrastructure while provincial laws prevent taxation that would cover the costs. Oil companies get a break on taxes as well, paying only 75 pre cent of what other businesses pay.

Plans for a rational development of the corridor have been in place for decades but have fallen on deaf ears. Recently, Van Nostrand’s firm prepared a plan for the Alberta government that would see a new town north of Fort McMurray with commuter hubs radiated from it.

Mid-Canada settlement corridor can take place with sustainable communities or continue in the current chaotic manner. It’s time we had that conversation with near-sighted and deaf politicians.